With all of the talk of The Great Resignation, it doesn’t come as a surprise that many people are asking the question, what do I really want to do?

Many people follow a guiding star throughout their early career. Their career transitions are based on what their parents or peers expected, what their peers did, where there was the highest status, or even taking what they were good at to its natural extreme. Later on, what they begin to question is whether that work is meaningful or significant to them.

In their book, “Designing Your Life”, Burnett and Evans define this as your “encore career,” or finding work that combines personal meaning, continued income, and social impact. Rather than follow the default path laid out by your previous achievements, maybe there is a way to have it all — meaningfulness AND feeding your family. In Designing Your Life, they address this search head-on by providing a framework to apply design thinking to life and career decisions. It’s based on their popular Life Design course taught at Stanford, which uses design principles and philosophies to create a program for assessing your life and moving forward.

Here are a few of the concepts I found most interesting and actionable from the book.

Where you are

My favorite takeaway from this book, and the one that I will regularly revisit for myself, is their intitial exercise challenging you to start by mapping out where you are.

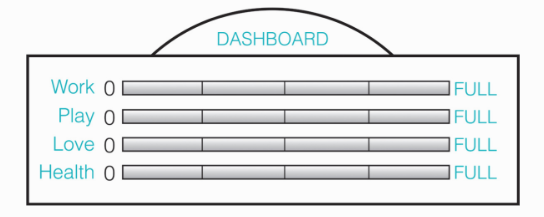

They present a simple health / work / play / love dashboard as a way to take stock of your current situation. The dashboard is a chart with gauges at 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100%. The directions are simple: make a list of your activities in each category and fill in the gauge based on how satisfied you are with it.

Each category is carefully defined:

Health — not just physical health, but an engaged mind and satisfied spirit.

Work — not just what you’re paid to do, but also include other duties such as second jobs, consulting, advising, volunteering, home-making, houseworking.

Play — any activity that brings joy just for the sake of doing it, which can include organized activities or productive endeavors so long as they’re done for fun and not merit.

Love — the health of your primary relationship, children, pets, community, or anything else tied to affection. Where is the love flowing in your life, from you or from others?

What I like about this framework is how thoughtful and inclusive the categories are. By explicitly calling out Play as anything that brings joy that is not Work, there’s a distinction made between activities you want to do and activities you have to do. They’ve redefined the category labels in a way that focuses on the impact and effect to you. After completing the exercise for myself, asking the question ‘What would I change here?’ was a powerful follow-up.

When I did this exercise, I definitely noticed how many items I had to list in Health and Work, and how relatively few I had in the category of Joy. It was a powerful moment of realization to compare the lists in each of these categories and notice where they were off from my ideal. I have a strong history of letting work take over my life, and it was an important check for me to think about how to prune my work commitments and set clearer boundaries on my time.

The power of the reframe

The application of design thinking is all about reframing how you define the problem and as a result the potential solution. It removes the filters and boxes you tend to put in place with problem-solving, by challenging us to view problems through a different lens. The argument overall is that this process helps us think more creatively about what to do with ourselves.

Instead of thinking about your work as a list of what you want from or out of work, Burnett and Evans ask you to think about it as what work is and what it means to you. Why work? What’s work for? What does work for? What defines good or worthwhile work? What does money, experience, fulfillment have to do with it?

Likewise, instead of thinking of your life as a list of activities and affiliations, they ask you to think about what values and perspectives define your understanding of life. Why are we here? What’s the point of family, country, and the rest of the world? What is the role of joy, work, justice, conflict in life?

What they’re getting at with their exercises is cultivating an environment of curiosity as to what the possibilities are. What if we were open to letting go of our limitations to explore other options open to us?

In my opinion, the most powerful reframe they had in the book is this idea of prototyping with your career. Instead of entering the next step of your career with an air of finality, they encourage the reader to think about prototyping conversations and prototyping experiences. What are the smaller more incremental steps that we can take to validate our interest and passion for bigger moves? If you’re interested in leaving your career as a software engineer to be a restauranteur, can you talk to people who are doing it? Can you host a few dinners and cook for friends? Can you set up a catering business? There are so many other paths to get there that don’t involve the wholesale leap that will still build confidence in the path forward.

Overall, I thoroughly enjoyed Designing Your Life and would recommend it as a thought-provoking read to anyone who’s exploring what next. Unlike many of the common structured frameworks out there, the questions and exercises throughout the book are well-designed to be open-ended and nurture creativity and curiosity.