Are we raising a spoiled child? I recently read Ron Lieber’s The Opposite of Spoiled: Raising Kids Who Are Grounded, Generous and Smart about Money and it was instantly one of the books that kept me up at night thinking and talking with my partner.

What am I afraid of as a parent? When I think about how we could screw up, I’m afraid of raising a child who is ungrateful, entitled, and lacking in motivation because we provided her with an environment of too much.

The definition of Spoiled

According to psychologist James Fogarty, the clinical definition of spoiled comes in four parts. Spoiled kids have these 4 attributes, but all don’t have to be present:

- Living a life with few chores and responsibilities

- There aren’t many rules to govern their behaviors and schedules

- Parents and others lavish them with time and assistance

- They have a lot of material possessions and extravagant experiences

He goes so far as to say that parents who overindulge their children can hinder their development into an adult.

At our current pace, our 4 year old daughter is trending toward spoiled. No chores, ample time, and lots of material possessions. The only redeeming quality I had is that we are fairly structured about our schedule and boundaries.

The rise of the fully provisioned child

There’s a modern trend in parenting which Lieber calls full provisioning. A fully provisioned child receives everything they could ask for in their parent’s power, the full kit of toys, enrichment, experiences, and clothes.

I see a lot of fully provisioned kids in the Bay Area (and we are guilty ourselves) and this book makes me wonder whether this is ultimately a harmful act. Seeking to shield them from the discomfort of being a “have not” in some cases is actually a healthy thing.

According to Lieber, we’ve shifted from seeing our children as “future workers” to the other extreme of “no expectation of usefulness.” In 1998, 45% of kids 16-19 had some part-time job and in 2023 that number has shrunk to 20%.

This is harmful because doing a job is what teaches grit and a work ethic. Kids like to work and seek it out. I wouldn’t want to rob my child of the experience of earning something through hard work. Moreover, if I’m so afraid of raising a kid lacking motivation, work is exactly how you learn it. How else will the incentives and mindset line up that work translates into results?

Helpfully, Lieber provides a number of suggested actions we can take to address this.

How and why to give your child an allowance

Lieber is a financial columnist, so naturally his lens on this is through money. He believes that teaching personal finance is a critical path for children to stay grounded in their adult lives. One of the first tools is an allowance, which he wants parents to start as early as children begin to ask questions about money. It’s his belief that allowances are a critical tool to learn patience and decision-making while stakes are low. He also strongly believes that allowances should not be tied to the completion of chores, which should not be compensated.

Here’s his allowance system:

- Start 1st grade at the latest, though there is no harm in sooner.

- Give $0.50-$1/week per year of age. So a 4-year old would receive $2-4/week.

- For younger kids, divide the money into 3 clear bins labeled Spend, Give, and Save.

- Give young kids an achievable savings goal and tape a picture of the item.

- As kids are older, the bins can become a virtual debit card. It’s also possible to add interest rates, matching, and other incentives.

- He discourages credit cards and instead suggests cash for younger kids and debit cards for older.

Having tangible money to hold and clearly divided bins begins to introduce the idea of a simple budget, while allowing them to make their own decisions. Then with the allowance system is in place, he introduces the concept of needs and wants.

Teaching Needs vs. Wants

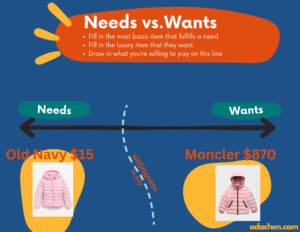

The idea of teaching needs and wants is teaching kids about the tradeoffs of how they can choose to spend money. I particularly like the exercise he describes because it’s easier to explain to a child. Here’s my own take with a winter jacket example –

Winter jacket example

Let’s imagine we are trying to buy a new winter jacket. Draw a horizontal line, labeling one side “Need” and the other side “Want”.

On the Need side, you can have a perfectly serviceable $15 jacket from Old Navy which will satisfy the need. On the Want side, you can have a $870 jacket from Moncler.

The next step is you draw a line on what your willingness to pay is. In his case, Lieber uses his “Land’s End line” which is the price equivalent of a Land’s End, which represents mid-range decent-quality article of clothing. This would be around $65.

The difference between the $65 and their wanted item must be funded from their Spend or Save budget.

By middle school, you can sit down with your child to create a budget of clothing items they need for the school year. After it’s priced out according to your willingness to pay, they receive a debit card with the amount pre-loaded to spend as they see fit.

While this creates some massive risk of blowing it all on a few items, he argues that giving them the power to make decisions is one of the most effective ways to learn.

Takeaways

Overall I think this book has been a reminder of how much influence we can have in our child’s development. Previously my mentality was a mix of helplessness and hopefulness that we’d manage to avoid spoiling our child, and there are so many great ideas in this book on how to actively foster life lessons.

What am I going to do differently because of it? Here is how I’m implementing this:

- Give her chores to do. I have now explained to her that now that she is 4, she has chores and a job to do just like we do. Her job right now is to clean up and put away her toys and books every night.

- Add an allowance sometime in the next year, most likely $1 per year of age per week following something similar to Lieber’s model.

- Determine where our own “Land’s End line” falls and be more intentional about not fully-provisioning.

In short, recommend this book if you’re a parent thinking through some of these questions yourself. The landscape of parenting has changed a lot since we were kids, and a lot of the valuable lessons I learned from watching my immigrant parents labor to make a life in America aren’t accessible to my daughter today. We need more tools, and this book offers many specific and interesting ideas on what to do.